Making the Work that Sees You

Artist Interview with Susie Epstein

Susie Epstein is one of those people who gives the soothing impression of belonging wholly to herself. The confident set of her shoulders radiates with the nurturance of her incredible (largely edible!) back yard garden, while the glow of her smile reflects the dancing fire of her creative spirit. She is a talented painter, a retired disability worker/social worker, and a long-time practitioner of Tai Chi and Kundalini yoga. I met Susie at a small gathering of Women-Identifying members of the Unitarian Universalist congregation (known as Wildflower Church), where Susie plays an active leadership role, and was immediately charmed by her warm confidence—and also by her darling sidekick, Marigold, a terrier-mix with a friendly but self-contained disposition that speaks to Susie’s steadfast care.

Like herself, Susie’s artwork is vibrant and engaging. Her paintings depict people and animals with evocative shifts in color that heighten the tenderness of the figure’s expression or position of the body. They are invitations to compassion and empathy, indicating the spirit behind the physical facade of her subjects.

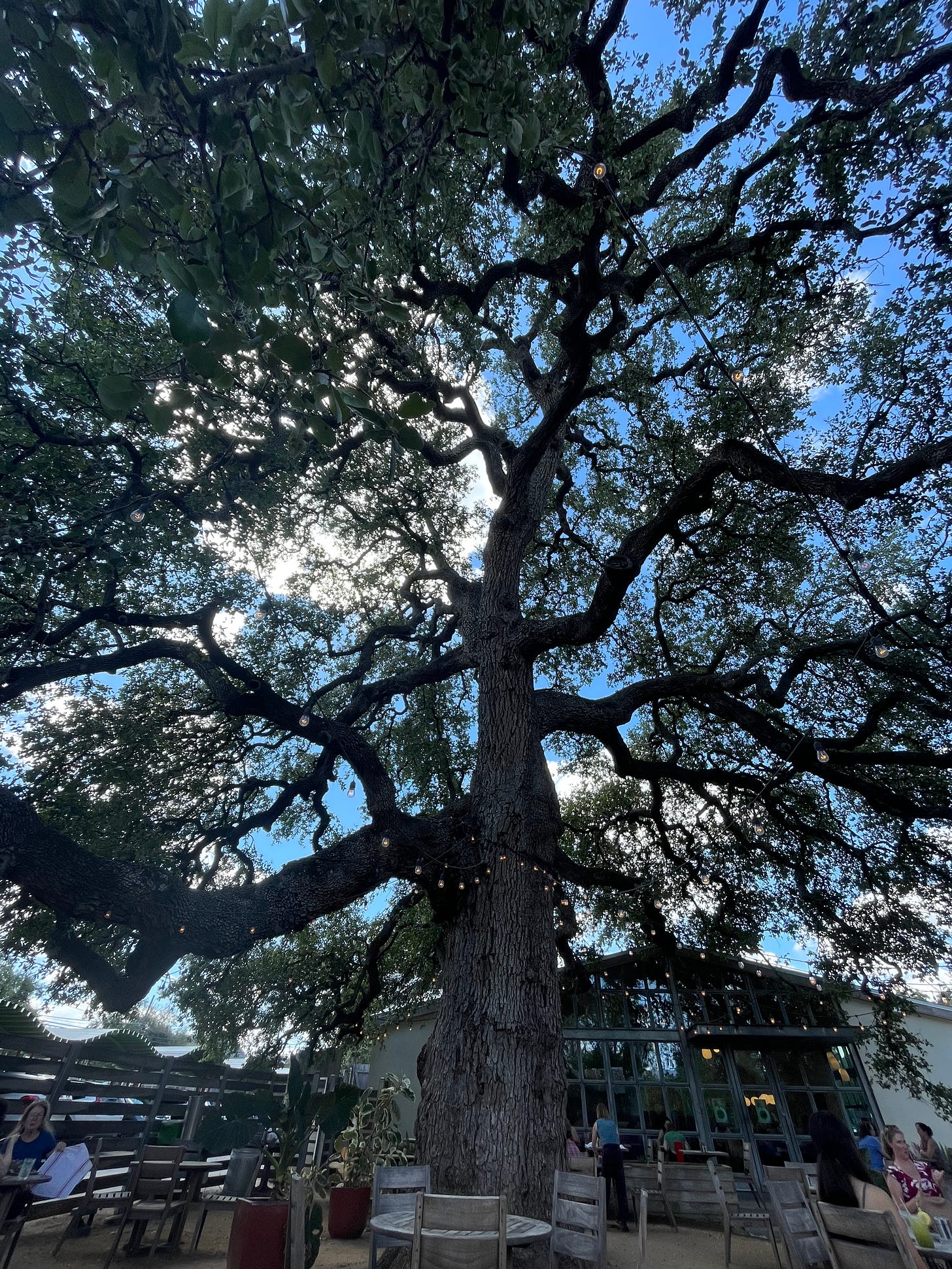

When I asked Susie if she would be willing to sit and talk with me for a while about the intersection of her spiritual and creative practices, she was (lucky for me!) receptive. We were quick to agree on the South Austin restaurant Vinaigrette, looking forward to its seasonal salads and the wide outdoor patio draped from above by the serpentine arms of an enormous live oak. As we talked, the sunlight drew a path through the branches, sending Susie and I shifting from one table to the next, in a clock-like rotation. Our server cheerfully followed us, saying this was common practice in the heat.

Susie started by sharing a reflection she wrote ahead of our meeting in which she explained that painting can be like meditation for her, creating a sacred space. It “reminds me of when I used to play the flute…” she wrote. “When you find you are just breathing, deeply breathing, and really only aware of yourself as a vessel for breath, and it is just pure bliss. It is an awareness of the profound sacredness of being alive.”

Because I know that Susie has extensively studied (and also taught) Kundalini yoga, I’m fascinated by her comparison. I have long felt a kinship between creative flow and meditation, ever since reading Natalie Goldberg’s dictum (borrowed from her teacher Katagiri Roshi) to: make writing your practice. But in my experience, flow feels less like a meditative state and more like a trance. I mean—do I even breathe when I am writing? I couldn’t say.

When I come out of a creative stupor I am aching, thirsty, light-headed, and usually desperate to use the bathroom. It’s something I’m working on: correcting my posture over the keyboard (hunched!), relieving my tendency to squint against the screen by wearing blue-light-blocking glasses, and setting alarms for bathroom breaks. But these are protective rather than integrative measures. I have found that if I want to invite my body into my creative practice, I have to leave my writing desk and do something different (sing, dance, or take another improv class).

Nonetheless, I resonate with Susie’s use of the word “vessel.”

I realize it’s an awkwardly intimate question, a kind of weird riff on the ones we’re supposed to pose to our toddlers to help them understand their feelings, but I have to ask her: what does it feel like in her body when she’s making art?

She’s kind enough to consider the question deeply. Looking up into the live oak’s branches, she appears to conjure the experience in her memory. She smiles. “I’m in a happy place. Just a very fun, happy place.” She has been working on a celebration-of-life drawing of a friend’s dear cat recently and she mimes holding her pencil in the air. Her eyes dance as she explains: “I’ve got the charcoal in my hand, I’m just glad to be there…it’s like, ok what’s gonna happen?…I really don’t know how it’s gonna come out.” Susie’s pencil hand transforms into a sheet of paper, which she holds out as if looking at her finished drawing. “And then I’m like, wow, this is really good. You did that really well.”

Her amusement with the culmination of her efforts has me smiling along with her. I relate to her description: the rising interest in a subject, the pull of possibility when your hand grips the pencil (or they hit the keys), the drop into ‘the zone,’ and then, finally, the (intriguing, if not delightful) surprise at the outcome.

Sipping her beet-juice mocktail, Susie explains to me that she began drawing at a young age, and had always been encouraged by her parents.

“When I was in grade school, I just drew people. My parents would have parties and some guest would be forced to stay there on the couch as I’d be drawing them. And everyone else would leave and the person couldn’t move for god-knows-how-long until I’d finish drawing them. And they’d be like ‘oh my god that’s so good!’ And my parents were so proud of me—that I could draw anyone.”

She tells me she has since been shocked to learn how many people suffer from what Brene Brown has called “creativity scars,” the lasting affect of moments, usually occurring in childhood, when people are told they aren’t ‘good’ writers, artists, musicians, dancers, etc. These events often calcify into fears that stifle creative expression and innovative thinking for years into adulthood.

“It’s so sad!” Susie exclaims. “We have to go back to crayons and drawings. Have a retreat.”

I agree that it’s a good idea, and we brainstorm for a while about different configurations of communal creativity: A parallel-play gathering where everyone brings their own easel or notebook to progress on their own work? Or a collaborative effort to craft a multivalent collage of group contributions? Susie prefers the former, acknowledging the benefit of shared accountability, but lamenting that working with others on a single project can mean “having to figure out: how does this fit in?” In solitude, she says, “You’re allowed to flourish without bounds.”

I think of our Virgo season reflection on the Hermit then and feel the draw of his fortifying light—the pulse of divinity that guides us in solitary endeavors. He knows that inviting outside influence into your process may offer creative expansion, but it is also likely to require compromise. Alas, the ‘reclusive artist’ did not become a trope by accident, and I tend decidedly toward that camp myself. But I wonder how much of this is a vestige of creative wounding. Or am I right in thinking that my most direct route to soul-level “Truth” runs through an inner landscape?

I feel that Susie and I are circling something important about the interplay of community and solitary practice. She shares about the feeling of effortless flow she experiences in practicing Tai Chi in a group setting versus the difficulty in maintaining the practice alone in her living room. I tell her what I learned about women’s bodies producing oxytocin when they bond in pairs or groups (as Susie and I were doing just then)—it’s the same hormonal release that occurs in a mother’s body while breastfeeding.

“The universal nursery!” Susie’s eyes widen in appreciation. “Our universal mother!” And—she continues—“Sisterhood: even if we’re not related, it’s being in the collective and keeping the group strong.”

Yes. Yes. And I’m inspired by the ways that Susie is living this: from serving as director for Wildflower Church’s Adult Religious Education, to her regular volunteer work at Faith Food Pantry, to the sacred attention that I know she works at applying in all of her day-to-day interactions with both people and her environment. “It’s just, shit gets in the way doesn’t it?” she says.

It does. I share with Susie about my long-term relationship with social anxiety and she tells me how she’s learned to honor her introversion. When she finds herself at a party thinking she’d rather be back home in her sweet house with her loving animals? She simply says good bye.

Maybe it’s the challenge of social connection that drives some of us back to our art, I think. It seems to offer another, potentially less fraught, portal for connection. As Susie wrote to me: “Painting is joyful for me… that place of creativity and being, of quiet in the natural world—especially if I am painting in my screened-in patio with the birds singing to each other and just being surrounded by my back garden…” Again I am reminded of the Hermit, that powerful archetype of seclusion in nature—like him, Susie has forged a deep connection with the non-human world. “What so far gives me the most joy…is when painting a beloved pet, when I see their adorable face and eyes looking back at me, I usually start giggling because I feel I have captured their very special spirit and that for me is pure joy.”

Susie’s delight, her heightened level of observation, her joy comes through in the paintings she creates: the animals’ eyes twinkle, their fur invites a touch. Many of her paintings serve a memorial function. Commemorative portraits of friends and animals that have died depict lines and planes invigorated by the exuberant beauty of the subjects’ embodied selves. Though they are created in solitude, Susie’s portraits celebrate points of connection, exploring “the beauty I see all around me,” in people, animals, in that which is alive. In her Self-Portrait with Marigold, she wears a Frida-inspired headdress of gold-finches and flowers, a bright sunflower opening over the crown of her head like a blessing, or a petaled third-eye. The figure’s physical eyes are downcast, but her nature, the painting suggests, observes all—including us—with keen, adoring insight.

As our lunch draws to a close, (I have to meet my kids after school and Susie has to return to Marigold), Susie gestures again to the branches of the massive live oak who has served as our host: “Just look at how the bark thickens along the bottom of each branch.” These shared observations are why I love having artistic friends. “Yes!” I say, touching my tricep. “They always remind me of the lower side of old women’s arms.” “You’ll get there!” Susie laughs with a hint of warning in her voice. “It’s beautiful!” I insist, and I hope that she is right.

We part on an effervescent note, buzzing with intentions for how we might share our creative joy with others: our UU church community and you dear readers of Arcana Craft.

Like a Hermit back from foraging herbs, I set the threads of our conversation to seep in the cauldron of my subconscious for the next few days. Over time they begin to swirl and bubble with images: Susie’s paintings, a raised hand holding an imaginary charcoal, the faces of friends and loved ones who have passed. The mixture starts to steam, and in the vapor a vision rises—of a memory and a wish.

But the story attached to them is much too long to tell now, and anyway it belongs to Scorpio season. If you’d like to hear it in November, please consider subscribing (it’s free) and becoming a part of this community of art-makers and spiritual-seekers. It would be an honor to have you here.

The art wants to be made, and it wants to be made by you

What a beautiful piece. For 50 years I have been blessed to be in sisterhood with Susie. She is an angel in my life, a creative light and an inspiration. I always come away from our times together sparked by a creative spirit, enthusiasm and surrounded by affection. This is a lovely piece of writing and a great gift to wake up to this morning.